A Close Reading of William Gibson’s “Agrippa” (part 3 of 3)

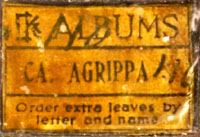

The link above is not to Agrippa, but to an important part of the poem: the linguistic and graphical codes extracted from the disk image by Freek Wiedijk— that is, the sequence of words arranged visually into line breaks, indentation, and stanzas, often referred to as the “text” of the poem– which has been in circulation online since it was posted on December 10, 1992. Why the text of the poem is more than just the words is discussed in my earlier postings: “Reading Agrippa” and “Agrippa as a Digital Object.” That being said, this posting will pay close attention to this linguistic text, keeping in mind the other texts and contexts that inform and complete this work known as Agrippa, and point out some meaningful patterns for readers to approach the poem with.

This autobiographical poem is divided into six parts, each of which focuses on a moment in the speaker’s life in which he becomes aware of the mechanisms that shape human experience, lending it the structure of a bildungsroman.

As a boy who discovers his deceased father’s Agrippa brand Kodak photo album he begins an exploration of his family history, relating to the photos as a boy used to chores might, observing things like “The grass needs cutting” and “Someone’s left a wooden stepladder out,” and imagining what tumbling down a large cone of sawdust would feel or smell like. Wood, its age and scent are prominent in this poem because they are powerful links to his rural past which he remembers more through smell– a sense closely tied to memory. In the second part, note how the discovery of an old gun, which twice fires by accident on this boy’s hands, “notched the hardwood bannister/ and brought a strange bright smell of ancient sap to life.”

Our speaker is older in the third part, and his examination of the photographs in the album demonstrate a different awareness of social and architectural mechanisms, such as the use of “charmless” “concrete and plywood” versus “sweet uneven brick that knew the iron shoes of Yankee horses.” Gibson contrasts horses as transportation vehicles of a rural past, with the cars his father knew (“1957 DeSOTO FIREDOME”) and those he came of age with (“Rocket Eighty-Eights”).

As a teenager in Toronto (in part IV), he is experimenting with guns, and becoming aware of the age and strength of different kinds of stone: the “limestone centuries” used to build “banks and courthouse,” the softness of a “shale pit” that can take bullets versus the “river rock” that can ricochet them back. These geological mechanisms resonate with the relative ages of cement, wood, and paper in this poem.

He shows awareness of race and racism in this and in part V, as he spends time in a bus station, expanded when the “colored restroom” was no longer needed because of the repeal of the Jim Crow laws. The extended magazine rack, where he found his calling as a writer, kept the mark of history by “smelling faintly and forever of disinfectant” and “of the travelled fears/ of those dark uncounted others.” It is in this space that we see the speaker understand the mechanisms of the law and its capacity to make people “dance/ or not to dance,” stop and go (in the traffic lights), remain or leave.

In the last part, the speaker goes off on his own, crossing national borders as light crosses the shutter on a camera into a space where it can inscribe its message. And yet the poem ends with a sense of freedom as the speaker finds himself in a larger world than he grew up in, experiencing cities like Toronto and Tokyo. Perhaps he has entered a larger, more complex mechanism, but his laughter signals that he knows how it works and is not afraid of what it will bring.

This poem is full of mechanisms: a camera, a gun, a bus station, and laws that govern segregation, international borders and they all have the power of “Forever/ Dividing that from this.” They all consist of enclosed spaces with openings that allow things to enter or exit obeying hidden processes, so it is fitting that the poem itself is a kind of “black box” from which a text emerges and into which it disappears without revealing its mechanism to readers.

The scheduled display serves three functions: it enforces a slow yet unstoppable reading pace, it creates anticipation for the next line, and it discourages rereading of the poem. This last one, combined with the poem’s self destruction, reinforces a singular experience of the text placing a burden on the reader’s memory to recall the poem– similar to experiencing life. And while one may inscribe one’s experience on paper, a computer, or photograph, what is produced is a crude mnemonic device, an extremely limited record of a rich reality full of sensory information and experiences.

And perhaps that is one thing Gibson, Ashbaugh, and Begos, Jr. sought to capture with their artist book and e-poem: a reminder of the evanescence of human experiences which can only be held in memory, despite the mechanisms we create to capture them.

Note: As should be evident from the links, these postings are built upon the ongoing research and documentation by Alan Liu and the team that created and lovingly continue to develop The Agrippa Files, and on Matthew G. Kirschenbaum’s writings and digital preservation efforts at MITH.

I look forward to producing a critical code reading of Agrippa, the day someone rises to the challenge and successfully cracks the code.